59 Westmoreland Place

PLEASE SEE OUR COMPANION HISTORIES

FOR AN INTRODUCTION TO WESTMORELAND PLACE, CLICK HERE

- Built in 1909 on Lot 61 and the southerly half of Lot 59 in Clark & Bryan's Westmoreland Place Tract by real estate developer William Franklin Young

- Architect: Frederick Noonan collaborating with Arthur Henrik Stibolt

- W. F. Young was an ambitious and confident native of north-central Iowa who had become a merchant there in the town of Clarion. Noting opportunity in the Oklahoma Territory, he moved to Oklahoma City in 1900 to pursue real estate and banking, in which he would make his fortune; he would later take part in the constitutional convention of the nascent state. In the meantime he had married Stella Peebles (pronounced "Pebbles") of Wisconsin in 1889 and had a daughter. Soon widowed or divorced, he married his sister-in-law. William and Alma Peebles Young together developed property in Oklahoma City even after moving west in 1907—the year Oklahoma became a state—soon setting up several real estate and construction entities in Los Angeles. Seeming to sample neighborhoods, the Youngs rented in the Westlake district before buying and flipping a house on Adams Street near Hoover; before moving to Westmoreland Place, they were renting the recently built 1910 South Harvard Boulevard in West Adams Heights

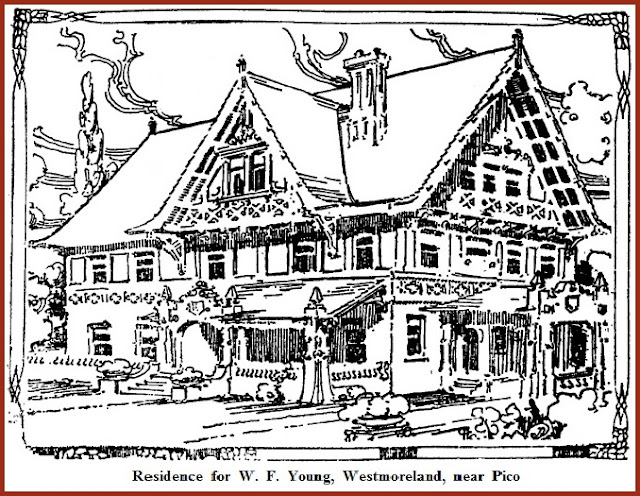

- A report of Frederick Noonan's plans for the Youngs at 59 Westmoreland Place appeared in the Los Angeles Herald on June 20, 1909. On August 8, the Times ran a rendering of the house and a description: "The structure is of the Elizabethan English style of architecture. A large porch of Utah white sandstone will be a feature. The body of the house is in plaster, half timber work and varnished redwood. The reception-room is to be finished in Circassian walnut, and the living and dining-rooms in English oak. The billiard room and den will be in India teak." On September 18, the Herald reported that the Young Construction Company would be building the 14-room dwelling

- The Department of Buildings issued a construction permit for 59 Westmoreland Place on September 17, 1909; on January 22, 1910, a permit was issued for the garage on which the Young Construction Company is given credit as both architect and builder

|

| As seen under construction in the Los Angeles Express on February 12, 1910; the view here is of the rear southwest corner of the house. The easterly drive of Westmoreland Place is at right. |

- The Youngs moved into 59 Westmoreland Place by the summer of 1910

- W. F. Young continued to build; in 1911, he began construction of the five-story reinforced-concrete Young Apartments that still stands hard by the 10 Freeway at the northwest corner of 17th Street and Grand Avenue. During 1920 and '21 he would participate in middle-class suburban developments including, with Fremont Place developer David Barry and heirs of the Rimpau family, the Wilshire Crest subdivision at the southwest corner of Wilshire and Rimpau boulevards, now called Brookside. Just to its west at the southeast corner of Wilshire and La Brea, Young platted his own tract, advertising it initially as "Youngstown." The name didn't stick, with part of it soon to be included in A. W. Ross's budding Miracle Mile. Both Wilshire Crest and Youngstown were aimed at drawing residents of aging West Adams and other westerly neighborhoods, such as those surrounding Westmoreland Place, piggybacking on the marketing of high-profile Hancock Park, also then just opening, as well as Fremont Place and Windsor Square, both inaugurated in 1911 and trying to regain momentum after Armistice Day and the postwar recession

- The stresses involved in his work spilled over at home in Westmoreland Place, a tract that was dying on the vine by the time Hancock Park and its adjacent neighborhoods were coming into their own. The Youngs separated, with Alma charging her husband with mental and physical abuse—and for using "language not becoming a gentleman"—ever since they married in 1896. W. F. wanted Alma out of 59 Westmoreland Place. She filed for separate maintenance, custody of 17-year-old William Jr., and for a restraining order against W. F. The Times and the Herald described the couple's wrangling over the Young Apartments and other city real estate, over thousands of acres of land in Kansas and more in Mexico, over stock in their real estate companies and in oil concerns, and, of course, over #59. While an out-of-court settlement was being reached—and before there was a reconciliation—W. F. did get Alma out of the house (she took an apartment at the Rampart at Sixth and Rampart, he one at the Young) and 59 was rented for a time to one of the biggest of Hollywood stars

- Buster Keaton and Natalie Talmadge were married in New York on May 31, 1921. His career was just taking off; she had appeared in D. W. Griffith's Intolerance but would have a lesser career than her sisters Norma and Constance. Finding 59 Westmorland Place available—and grand enough for the socially ambitious Natalie—they rented it from W. F. Young on their return to the west coast while deciding where to live. The elder of the Keatons' two sons, Joseph, was born on June 2, 1922, while they were living at #59, and that year Keaton made use of the house as a backdrop in his comedy short The Electric House, released in October. When the Youngs settled their differences and announced that they wanted their house back, the Keatons bought 637 South Ardmore Avenue in January 1923. (Keaton and Talmadge owned 637 South Ardmore for just 10 months; after managing to make a considerable profit by selling it for $85,000, they moved on to 543 Muirfield Road in Hancock Park—yet another stop before Buster built a famous Beverly Hills house, completed in 1926, in a fruitless effort to please his notoriously avaricious wife)

|

Buster Keaton made ample use of his rental of 59 Westmoreland Place; during 1922 he filmed his short The Electric House, starring Keaton as a botany major accidentally given the diploma of a graduate in electrical engineering. Assuming that this conferred upon him abilities he didn't actually possess, he transformed the dean's residence into an electrical wonderland that predictably turns into a comic nightmare. Detail of the porchfront arch is seen above; note the carriage block still in place. |

- Once back at 59 Westmorland Place, William and Alma Young stayed in the house even as the neighborhood became more isolated socially as the affluent moved west during the '20s to Wilshire-corridor suburbs all the way out to Pacific Palisades. With only nine houses ever built within its gates—the last in 1911—wrangling over the proper use of Westmoreland Place properties, whether to allow apartments to be built or for its empty acres to be developed by the city as a park, continued until the late '20s. Finally, not only would apartment buildings be allowed, but the Place's elaborate gatehouse entrances were demolished, its exclusivity then lost completely when the easterly roadway between Olympic and Pico boulevards became merely another stretch of Westmoreland Avenue, renumbered as such, the westerly roadway similarly becoming just another couple of blocks of Menlo Avenue. The Youngs' new address became 1229 South Westmoreland Avenue

- Remarkably, despite its early promise having been derailed, most of Westmoreland Place's homeowning families were still in their houses when Wall Street laid its egg, with the Johnsons, Threshers, Bryans, Mileses, Clarks, Carrs, and Wellses in addition to the Youngs all holding firm even with their social cohort having fled to districts such as Hancock Park, Beverly Hills, Bel-Air, Holmby Hills, Brentwood and farther afield. The hard times finally forced them to surrender, their white elephants now suitable only as apartments, rooming houses, meeting spaces, and a form of housing to become particularly common in the Pico Heights area, sanitariums

- In a curious small display advertisement in the Times on March 6, 1927, W. F. Young sought a three- to five-year $100,000 loan secured by one of his downtown holdings, presumably for a new real estate or oil venture

- Though even as the Depression descended the Youngs decided to keep the house in their real estate portfolio—buyers would in any case have been scarce—1229 South Westmoreland Avenue would be going through several public and commercial phases after they decided to shutter it for the time being and move to the Young Apartments in 1932. In 1935, the Young People's Hebrew Association began renting 1229, holding a dedication ceremony on May 16. The Youngs were by this time living at the San Marino Villas at the southeast corner of San Marino Street and Serrano Avenue

- On January 25, 1929, restrictions against multi-unit housing in the Westmoreland Place Tract were finally rescinded. On May 3, 1931, the Times reported that the first apartment structure within the original boundaries of the subdivision had just opened; the five-story Art Deco Crestwood, still standing at 1036 Menlo Avenue, was the first of dozens of apartment buildings that, after the economic doldrums of the '30s, would begin to line the empty lots of the tract over the next couple of decades. The first of four eight-family units just north of 1229 went up in 1939; a 24-unit block rose next door to the south in 1948

|

An aerial image made on January 1, 1928, reveals the nine houses built in Westmoreland Place; the Young house is indicated by a red arrow, as it is in the comparable view below taken on October 1, 1962. The only one of the nine in place today is #156, now addressed 1218 Menlo Avenue, which is the house seen nearest to the Young in the 1928 view. The roadway at bottom is Vermont Avenue, with Olympic and Pico boulevards to the left and right. The pale strips in the middle are the two streets of Westmoreland Place, at the ends of which can be seen some evidence of gatehouses only recently removed. |

- Despite the neighborhood now being given over to new multi-unit housing, the Youngs' 1229 South Westmoreland Avenue would hold on for decades. The family itself would retain possession well into the 1950s

- The Young People's Hebrew Association left 1229 South Westmoreland in 1938, on October 18 of which year the Department of Building and Safety issued the Youngs a permit to convert the residence into a guest house. It would be called Westmoreland Manor. A classified ad for it in the Times on May 31, 1941, reads in part, "Beautiful home. Fine meals. Lovely grounds. Billiards, ping-pong. P car." ("P car" refers to the proximity of the Los Angeles Railway's Pico Boulevard line.) A permit issued to W. F. Young on June 25, 1943, allowed for two 24-foot-long wooden ramps to be added to the house to convert it into a "rest home"; "sanitorium" was the term used on a permit issued the following October 19 to build a stairway from second-floor porches to the ground at the behest of the L.A.F.D. There are references in the press to 1229 now being a facility for dipsomaniacs

- On October 9, 1951, Alma M. Young was issued a Certificate of Occupancy by the Department of Building and Safety changing the use of 1229 South Westmoreland from a "Sanitarium" to a "Boarding Home for the Aged." It was renamed "Robins Manor" and in 1953 housed 25 women

- The Youngs were living in Laguna Beach when W. F. died on March 4, 1953, two weeks shy of his 86th birthday. On December 27 of that year, Ruth Young Armstrong was seriously injured when fire broke out in her Hollywood home. She died two days later; her obituary in the Times on December 31 referred to Alma Young as her stepmother. The Youngs' daughter Blanche Young Raymond had died in 1940. Living with a granddaughter in Fontana but still the owner of 1229 South Westmoreland, Alma Maria Peebles Young died at Loma Linda Hospital on April 19, 1955

- On September 18, 1953, Alma Young had been issued a permit to enclose a porch of 1229 South Westmoreland; she was issued a Certificate of Occupancy for this work posthumously on October 11, 1955

- Precise ownership of 1229 South Westmoreland Avenue after the death of Alma Young is unclear. The house continued to be run as Robins Manor into the 1970s. By 1974, there was a new tenant: Narconon, a substance-abuse treatment facility claimed in the Times of June 7, 1974, by its operator—an avowed Scientologist—not to be affiliated with his church. (Other sources dispute the lack of a connection.) The Times article makes reference to the house once having been the home of Buster Keaton

- On a permit issued by the Department of Building and Safety on May 6, 1977, a Masara Kamatana is listed as the owner of 1229 South Westmoreland; Kamatana is described on the document as intending to convert the house back to a single-family dwelling

- Demolition permits for 1229 South Westmoreland Avenue and its garage were issued by the Department of Building and Safety to a Bob Nelson of Glendale on June 4, 1979; on September 28, 1984, a permit was issued to a new owner for the construction of a three-story, 41-unit building to serve as low-income senior housing

Illustrations: LAT; LAH; LAE; Press Reference Library; Hollywood Forever;

John Bengtson's Silent Locations; UCSB Library

John Bengtson's Silent Locations; UCSB Library